Freight, Mobility, Community

April Schneider, Emily Valentino, Patricia Roche 2020 Fall Fellowship

“Like an operating system, the medium of infrastructure space makes certain things possible and other things impossible. It is not the declared content but rather the content manager dictating the rules of the game in the urban milieu.” Keller Easterling, ExtraStateCraft. The surface transportation system in New York City is the result of technological innovation that created cars and a planning paradigm that then prioritized them. Its vast networks of urban highways, streets, and traffic control systems were calibrated to provide throughput efficiency for vehicles. A century after the first car hit the road, we are grappling with the impacts of car-centric design: high asthma rates tied to air pollution, climate change tied to carbon emissions, mental health issues related to chaotic traffic and noise pollution, a growing safety crisis that leaves more pedestrians and bicyclists killed or severely injured each year, and environmental and mobility injustice – where communities of color bear the burden of all of the above more than any other demographic.

These issues force us to look differently at the highways threading through our cities. While the permanence of transportation infrastructure renders it a de facto part of daily life in America; in fact, we can decide differently. We must recognize that transportation

infrastructure is not simply enabling us to move; it is also dictating how we move. In other

words, when we choose to build a highway instead of a rail line, we make driving the

infinitely better – and often only – choice.

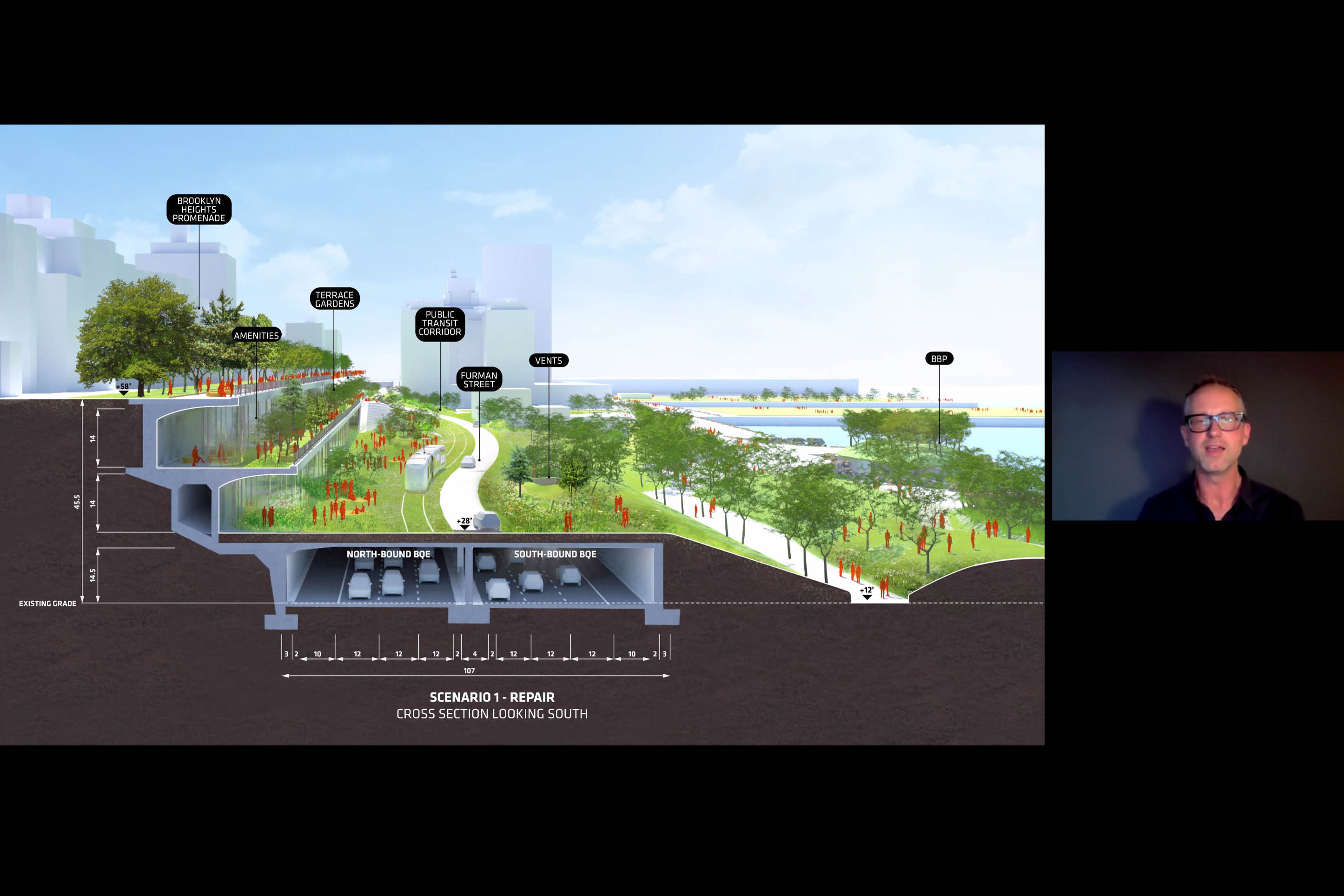

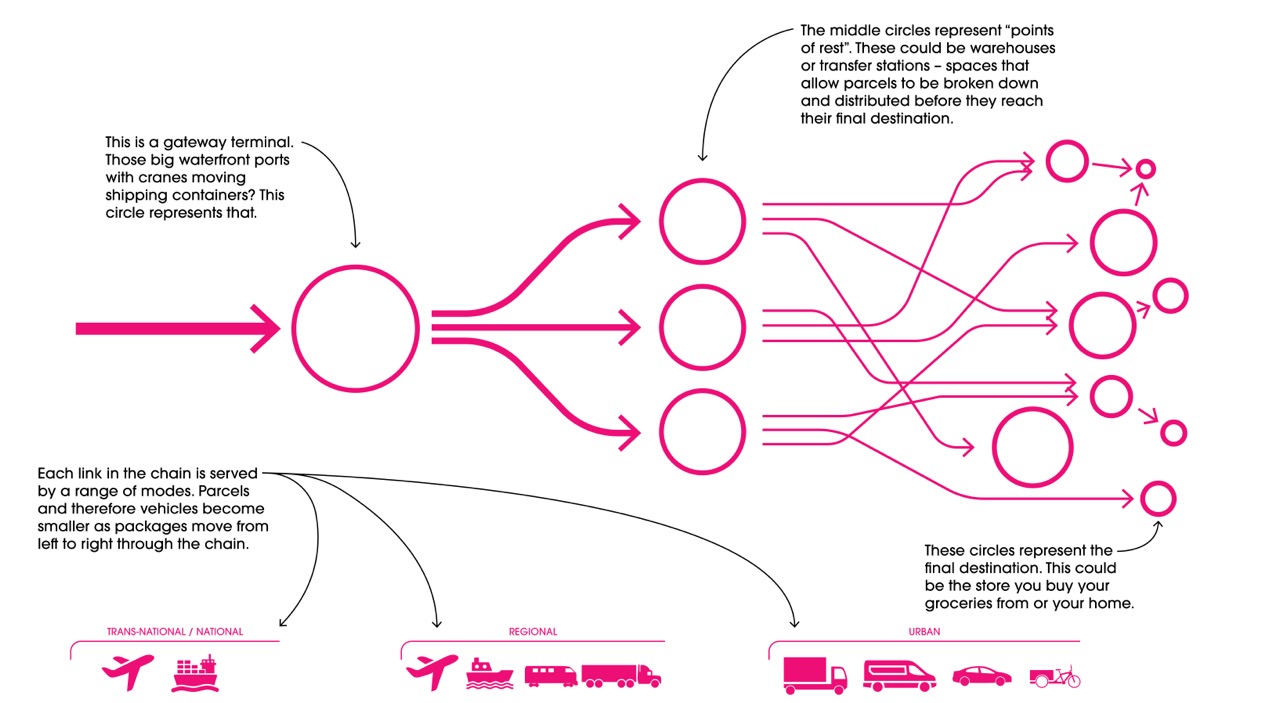

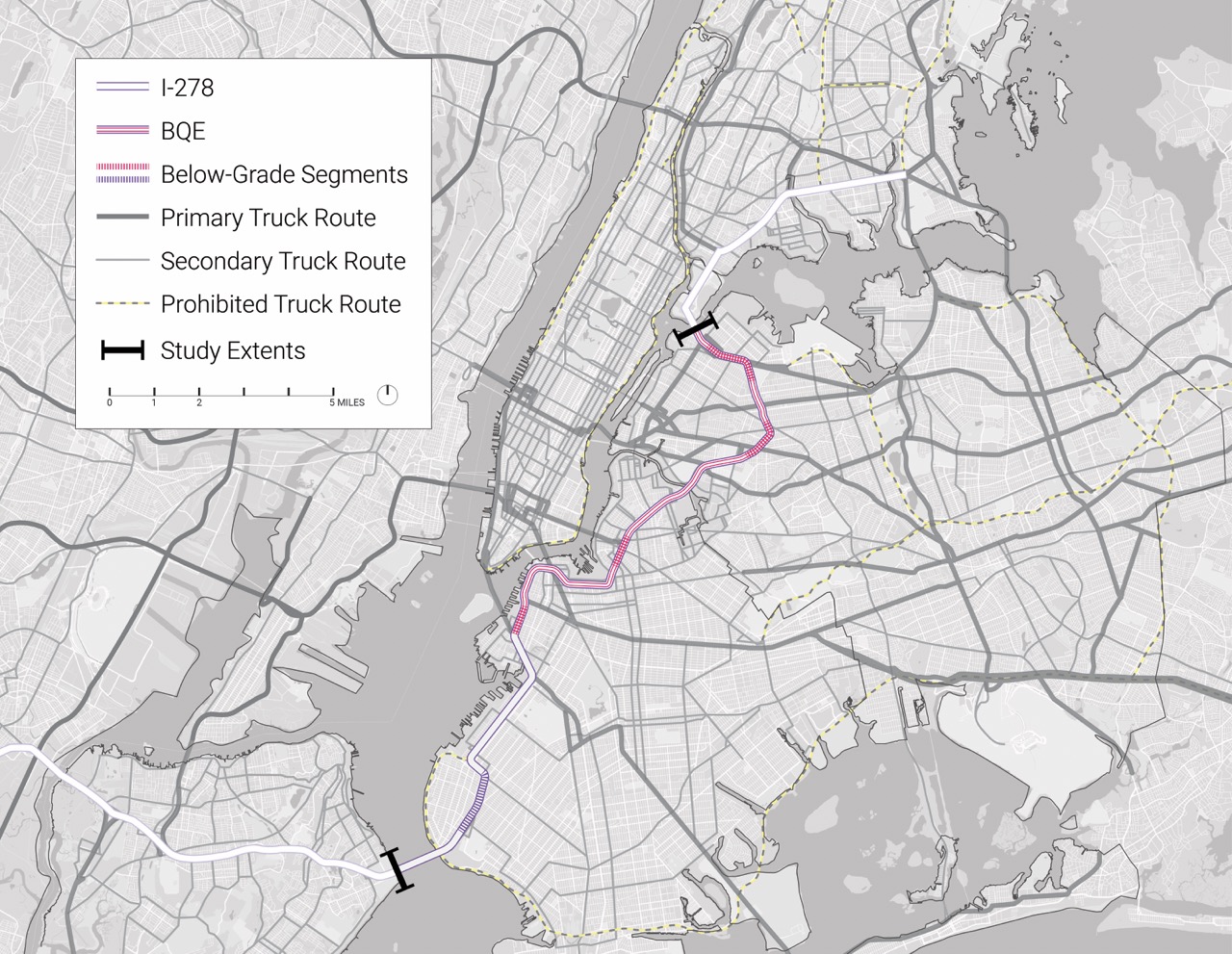

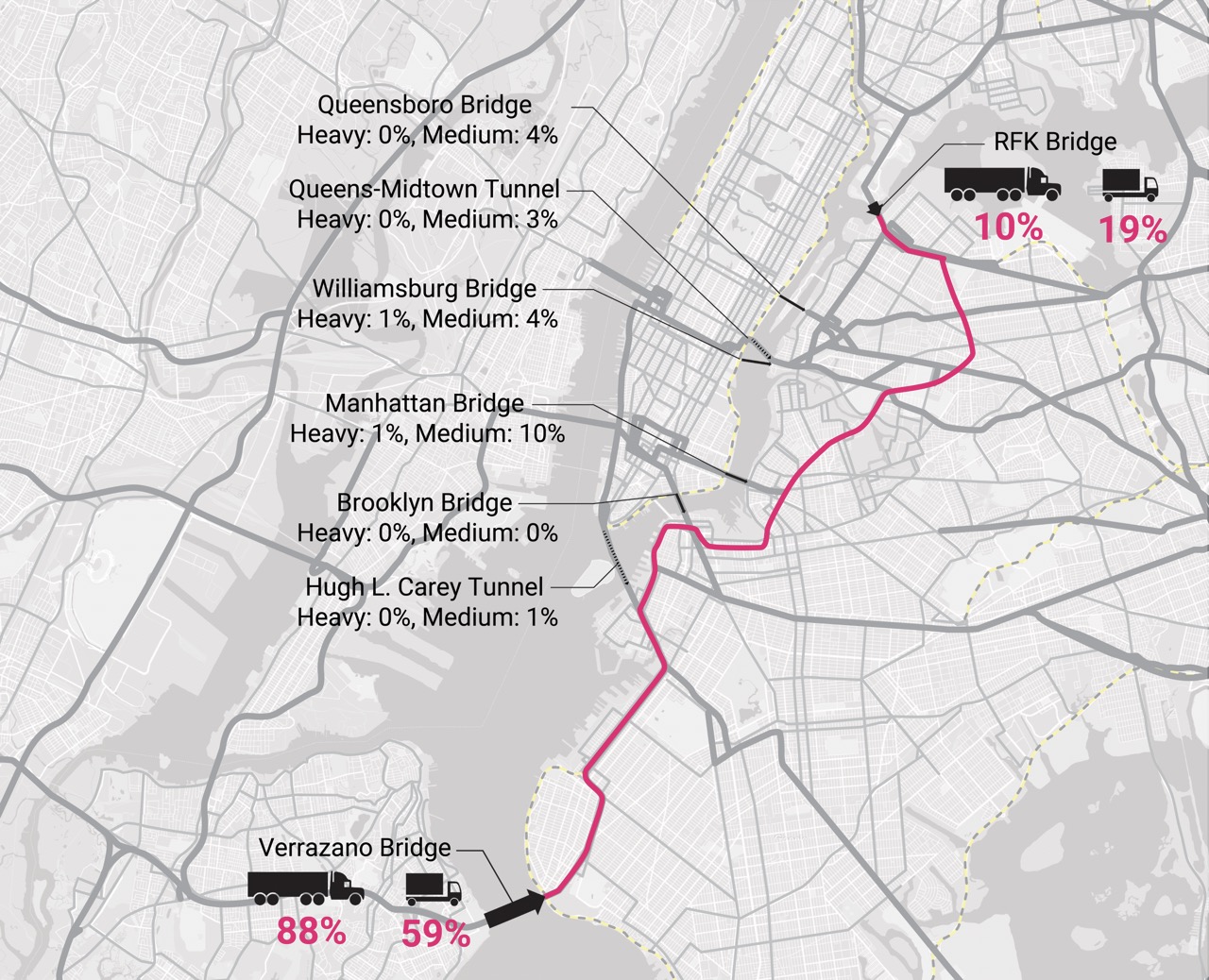

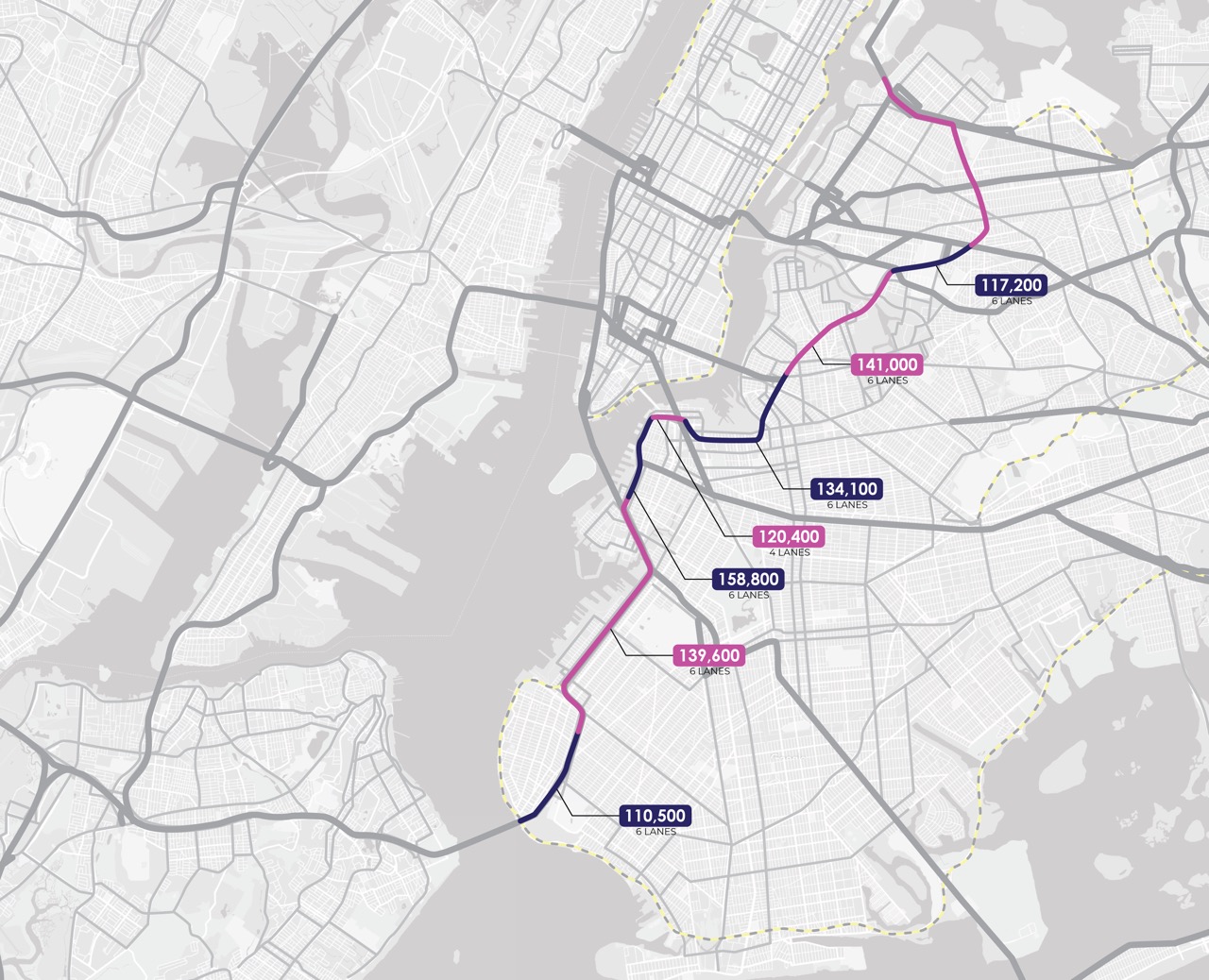

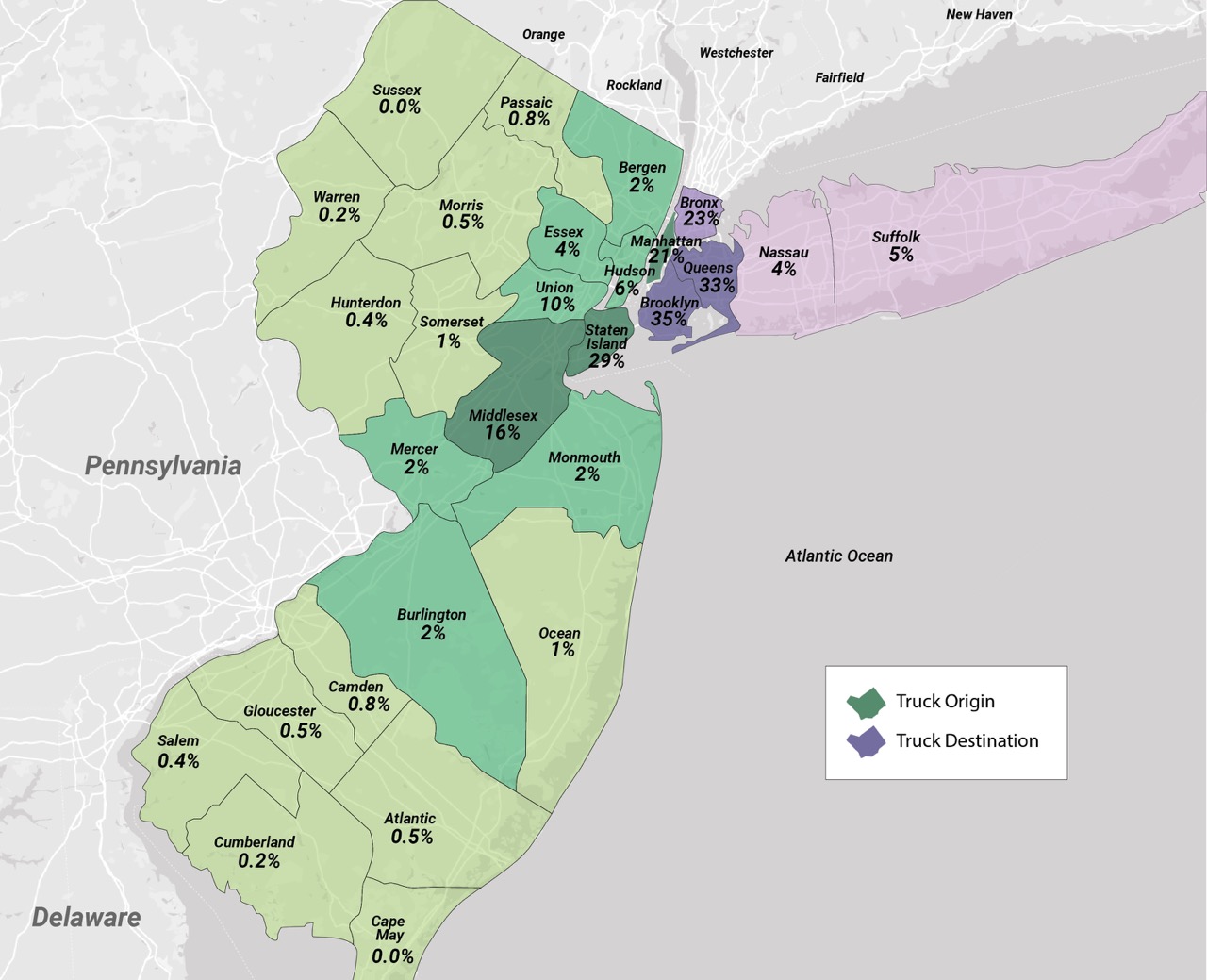

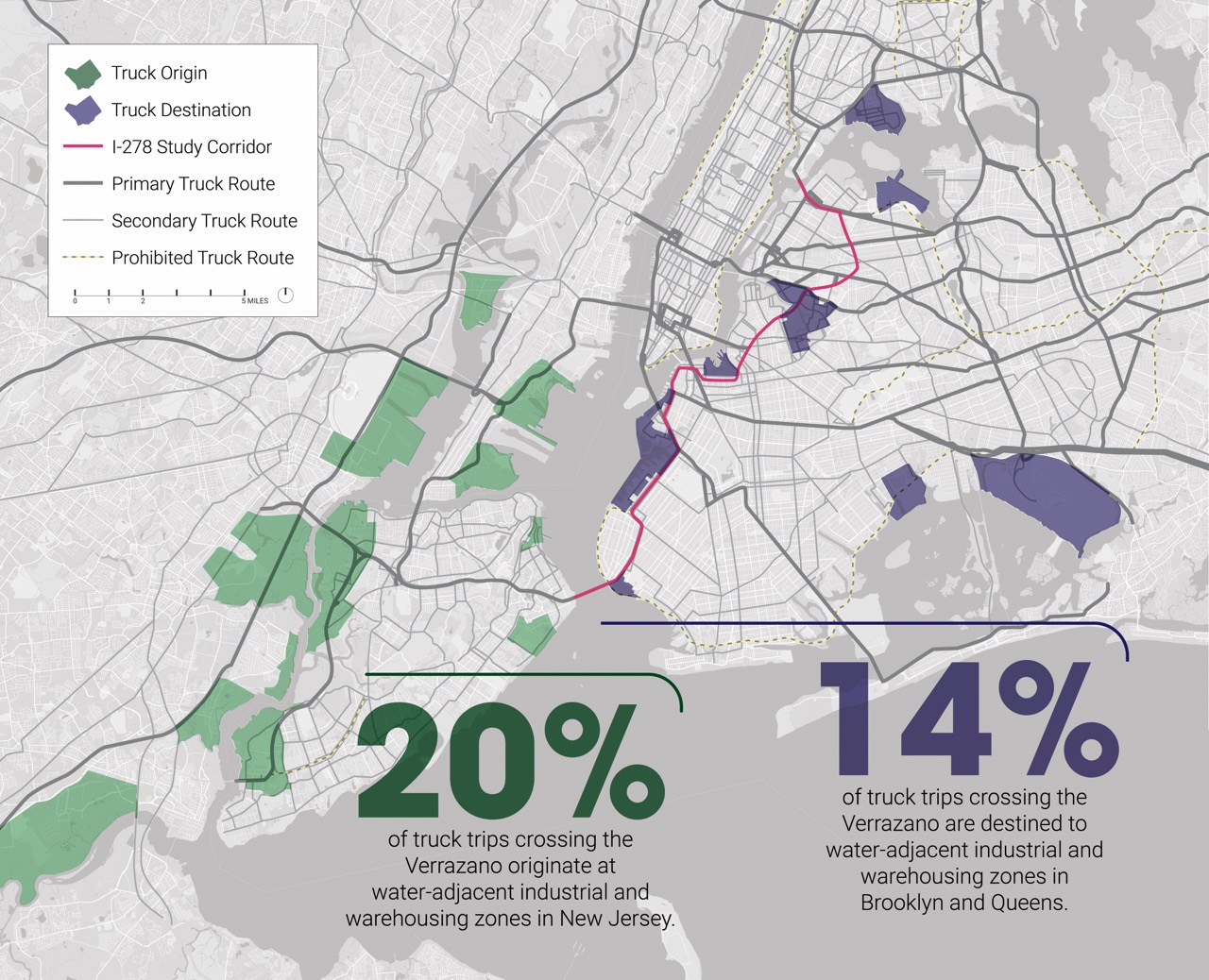

The BQE was built and broadened within this 20th century archetype, and as we begin to rethink its role in the urban transportation system, it is critical that we understand its role in the urban freight network also. As the only major (and legal) north-south truck route through Brooklyn and to Queens, it has come to be an essential part of goods movement. More than 20,000 trucks use it to move goods into and out of Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island every day, accounting for 89% of goods movement in the region.

But the BQE is more than complicit in shaping the way goods move in New York City – it is a culprit, and our reliance on it is not a mere accident; it is by design. To deconstruct a

highway, then, we must first deconstruct the common narrative that the BQE is the only

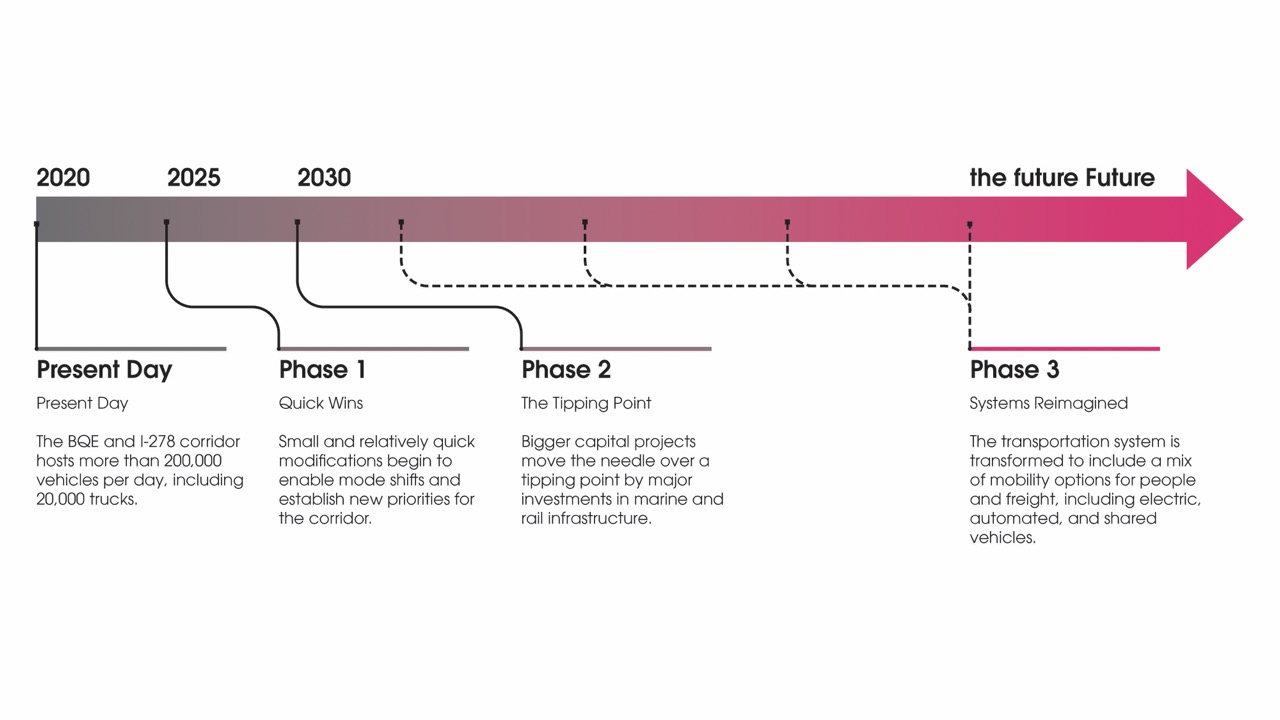

option for moving freight. This study sought to answer two key questions: 1) what is the

actual opportunity to shift away from a truck-based freight system based on the geography of goods movement in New York, and 2) what would a gradual approach to inducing such a shift look like?

These issues force us to look differently at the highways threading through our cities. While the permanence of transportation infrastructure renders it a de facto part of daily life in America; in fact, we can decide differently. We must recognize that transportation

infrastructure is not simply enabling us to move; it is also dictating how we move. In other

words, when we choose to build a highway instead of a rail line, we make driving the

infinitely better – and often only – choice.

The BQE was built and broadened within this 20th century archetype, and as we begin to rethink its role in the urban transportation system, it is critical that we understand its role in the urban freight network also. As the only major (and legal) north-south truck route through Brooklyn and to Queens, it has come to be an essential part of goods movement. More than 20,000 trucks use it to move goods into and out of Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island every day, accounting for 89% of goods movement in the region.

But the BQE is more than complicit in shaping the way goods move in New York City – it is a culprit, and our reliance on it is not a mere accident; it is by design. To deconstruct a

highway, then, we must first deconstruct the common narrative that the BQE is the only

option for moving freight. This study sought to answer two key questions: 1) what is the

actual opportunity to shift away from a truck-based freight system based on the geography of goods movement in New York, and 2) what would a gradual approach to inducing such a shift look like?