From Hacking to Housing

Amy Breedlove, Jeffrey S. Nesbit, Samir S. Shah

2020 Fall Fellowship

From Hacking to Housing reframes the problem from the collaborative perspective of a

community advocate, an architect, and an urbanist, committed to equitable solutions for

elevating the quality of the built and ecological environments. Since the announcement of

Robert Moses’ grand plan to cut through neighborhoods and build a highway in the 1930s,

the questions of equity and access have plagued communities along the BQE corridor.

Through political and economic power, Brooklyn Heights won a hidden highway with a public

park above it. Other neighborhoods, without the same influence, were severed and divided

by the BQE.

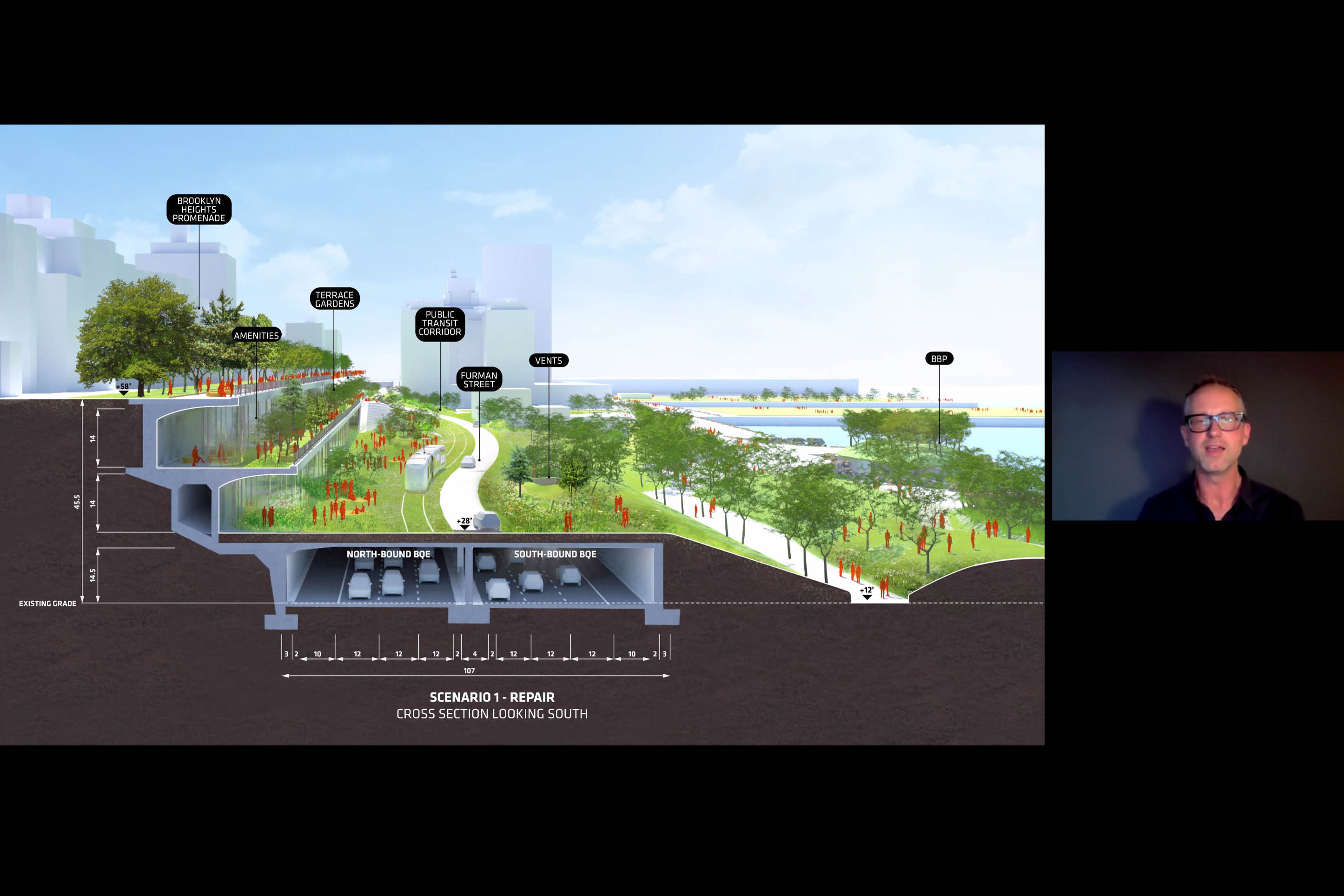

Seventy years later, the unique engineering feat known as the “triple cantilever” that served

to protect Brooklyn Heights’ historic district from the full effect of an adjacent highway is at

the end of its lifespan. Ultimately, responsibility and jurisdiction for the segment of the BQE

between Atlantic Avenue & Sands Street lie solely in the hands of NYC. Eventually, scope,

scale, and jurisdiction for this segment of the BQE lie solely in the hands of New York City.

The City got to work, and NYC Department of Transportation came up with two plans,

respectively labeled, "traditional" and "innovative.” Again, the Brooklyn Heights community

felt their parks, property and way of life would be compromised, and they sprang into action.

The community organized to protect their backyards and the now beloved Promenade Park

at the top of the cantilever. Yet, residents didn't want a so-called “innovative” plan to put a

six-lane highway and cars outside their windows. No one wants an elevated highway outside

of their window. No one wants to exercise or have their children play in a park next to a

highway that moves 150,000 vehicles a day, no one.

The BQE has been a divider more than a unifier since its earliest planning stages. Robert

Moses saw progress as movement increased from one neighborhood to another using

personal automobiles—and responding with the design of a north/south corridor to enact his

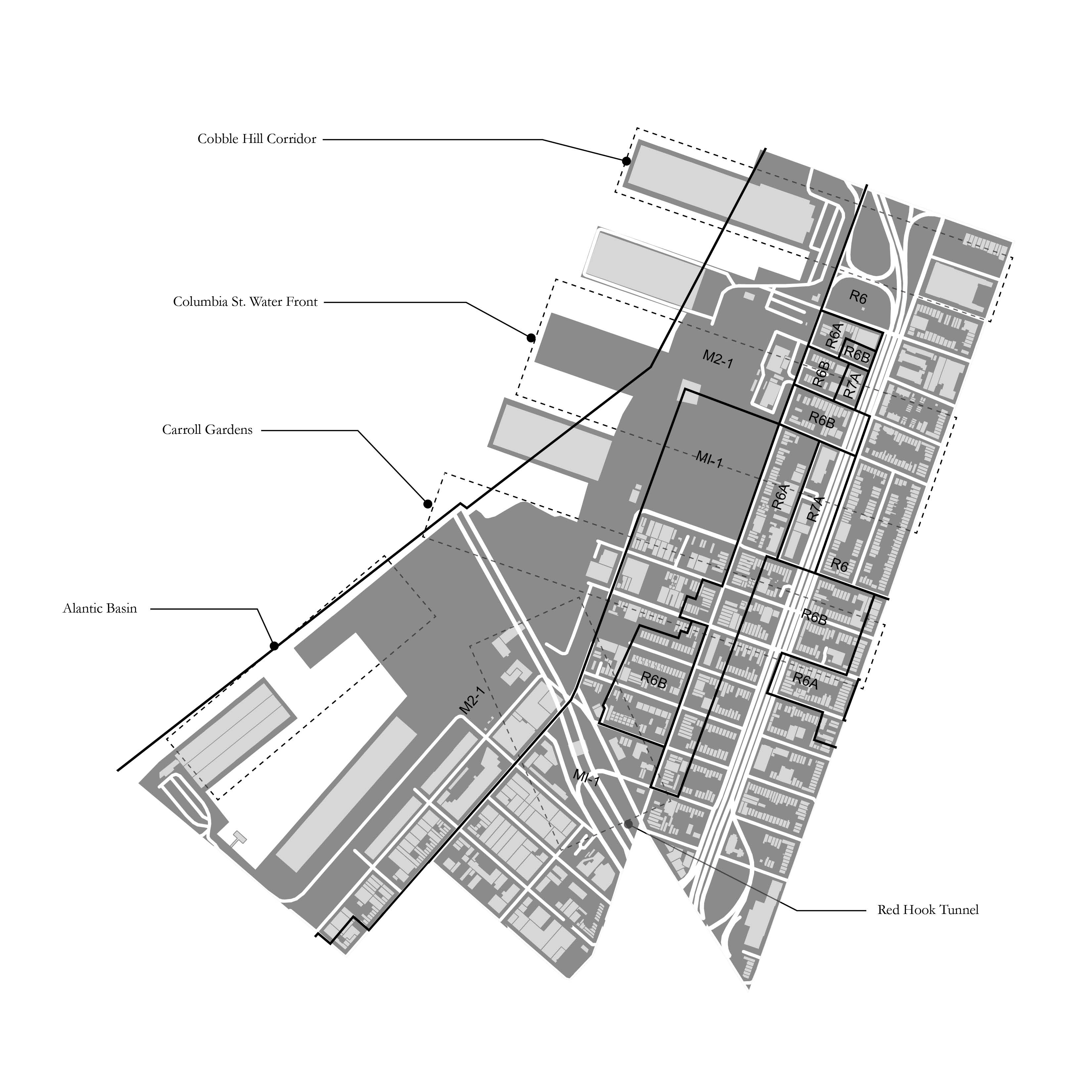

vision. Life in Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens Brooklyn flowed from east to west, from the

houses up on the hill, past the commercial strip along Hicks Street, to the working waterfront.

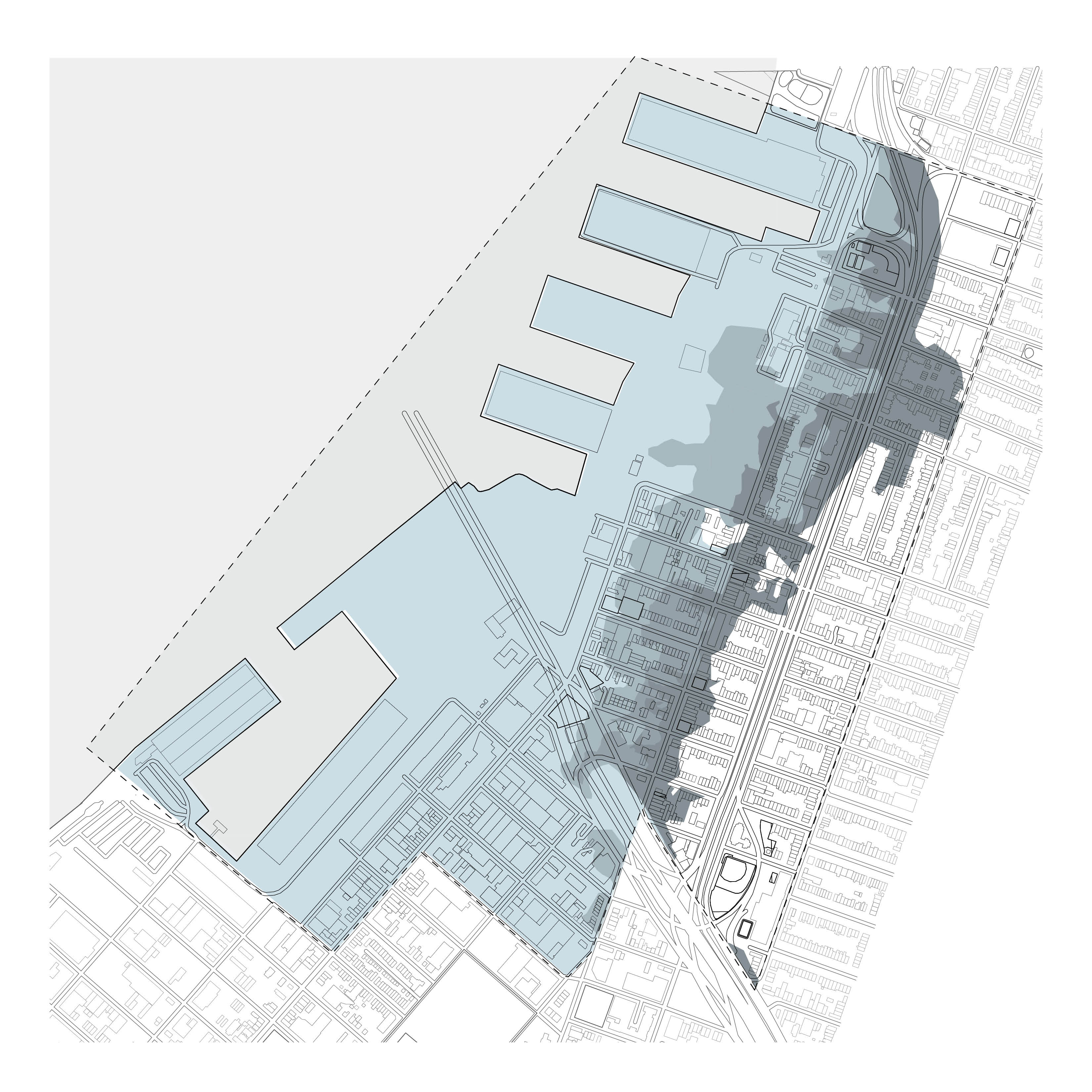

When the BQE trench was cut, the east/west connections were severed. Red Hook was

isolated behind the highway and a new tunnel allowed cars a faster way to enter the financial

district in lower Manhattan. Its potential for growth was sacrificed for a “masterplan” made

from engineering solutions for speed, efficiency, and a rise of urban modernity.

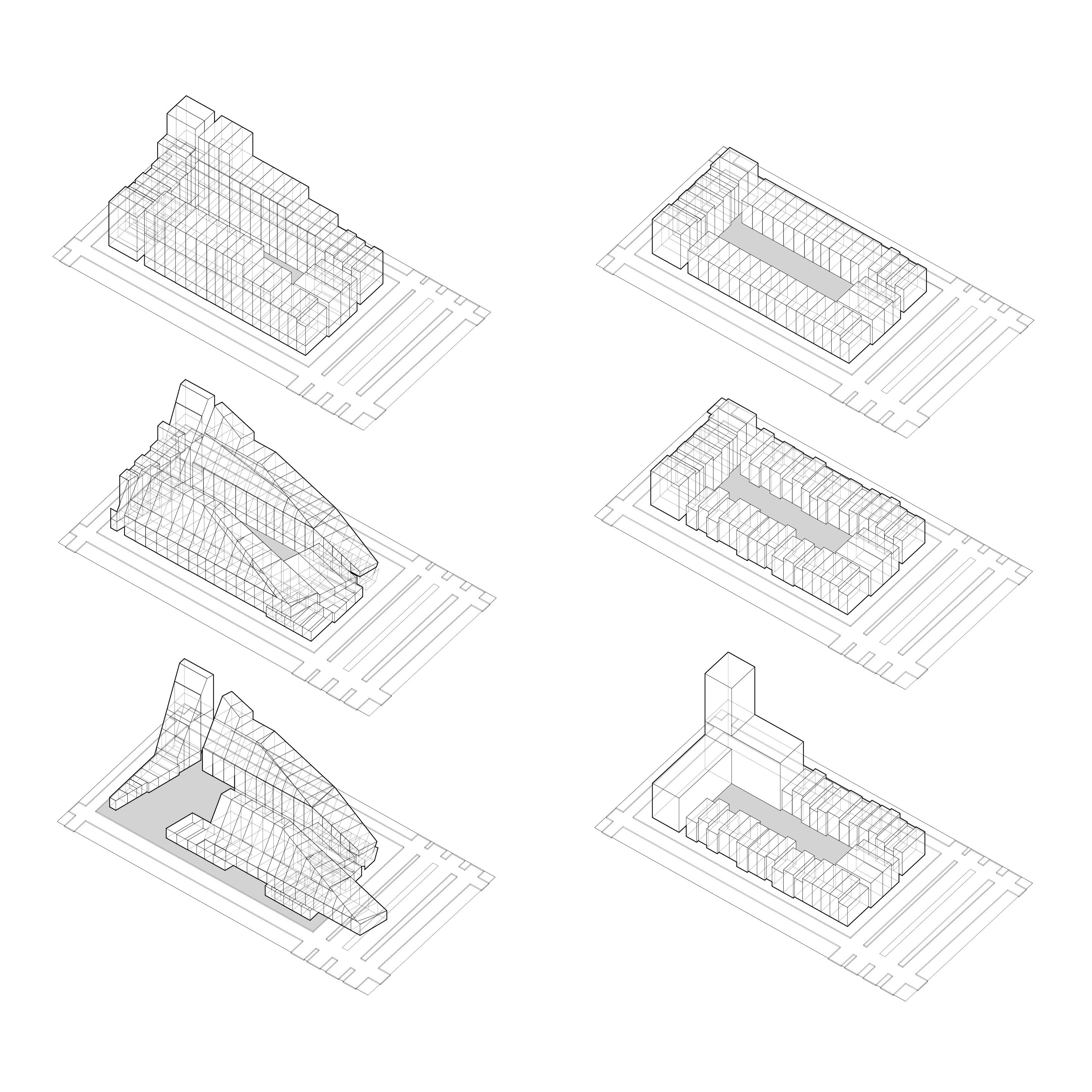

Many designers and groups came forward with alternate designs for the “triple cantilever.”

The focus remained on this stretch of the BQE less than a mile long. But what about

neighborhoods to the north or to the south? A trench or an elevated highway has severed

these neighborhoods for decades, which has limited access to public transportation and

other vital public amenities and services that contribute to economic growth, eliminating

vibrant commercial corridors and creating harmful environmental effects. If long-term

planning and a new vision for our future are not enacted, these neighborhoods will continue

to suffer inequity for another century to come.

community advocate, an architect, and an urbanist, committed to equitable solutions for

elevating the quality of the built and ecological environments. Since the announcement of

Robert Moses’ grand plan to cut through neighborhoods and build a highway in the 1930s,

the questions of equity and access have plagued communities along the BQE corridor.

Through political and economic power, Brooklyn Heights won a hidden highway with a public

park above it. Other neighborhoods, without the same influence, were severed and divided

by the BQE.

Seventy years later, the unique engineering feat known as the “triple cantilever” that served

to protect Brooklyn Heights’ historic district from the full effect of an adjacent highway is at

the end of its lifespan. Ultimately, responsibility and jurisdiction for the segment of the BQE

between Atlantic Avenue & Sands Street lie solely in the hands of NYC. Eventually, scope,

scale, and jurisdiction for this segment of the BQE lie solely in the hands of New York City.

The City got to work, and NYC Department of Transportation came up with two plans,

respectively labeled, "traditional" and "innovative.” Again, the Brooklyn Heights community

felt their parks, property and way of life would be compromised, and they sprang into action.

The community organized to protect their backyards and the now beloved Promenade Park

at the top of the cantilever. Yet, residents didn't want a so-called “innovative” plan to put a

six-lane highway and cars outside their windows. No one wants an elevated highway outside

of their window. No one wants to exercise or have their children play in a park next to a

highway that moves 150,000 vehicles a day, no one.

The BQE has been a divider more than a unifier since its earliest planning stages. Robert

Moses saw progress as movement increased from one neighborhood to another using

personal automobiles—and responding with the design of a north/south corridor to enact his

vision. Life in Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens Brooklyn flowed from east to west, from the

houses up on the hill, past the commercial strip along Hicks Street, to the working waterfront.

When the BQE trench was cut, the east/west connections were severed. Red Hook was

isolated behind the highway and a new tunnel allowed cars a faster way to enter the financial

district in lower Manhattan. Its potential for growth was sacrificed for a “masterplan” made

from engineering solutions for speed, efficiency, and a rise of urban modernity.

Many designers and groups came forward with alternate designs for the “triple cantilever.”

The focus remained on this stretch of the BQE less than a mile long. But what about

neighborhoods to the north or to the south? A trench or an elevated highway has severed

these neighborhoods for decades, which has limited access to public transportation and

other vital public amenities and services that contribute to economic growth, eliminating

vibrant commercial corridors and creating harmful environmental effects. If long-term

planning and a new vision for our future are not enacted, these neighborhoods will continue

to suffer inequity for another century to come.